IDEOLOGY

Date: 2015-10-07; view: 689.

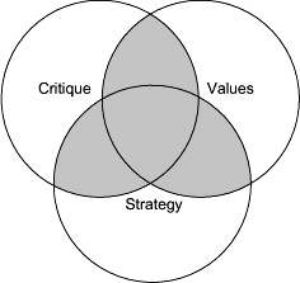

Ideology is one of the most contested of political terms. It is now most widely used in a social-scientific sense to refer to a more or less coherent set of ideas that provide the basis for some kind of organised political action. In this sense all ideologies therefore, first, offer an account or critique of the existing order, usually in the form of a ‘world view'; second, provide the model of a desired future, a vision of the ‘good society'; and, third, outline how political change can and should be brought about (see Figure 2.1). Ideologies thus straddle the conventional boundaries between descriptive and normative thought, and between theory and practice. However, the term was coined by Destutt de Tracy (1754–1836) to

Figure 2.1 Political ideology

Figure 2.1 Political ideology

describe a new ‘science of ideas', literally an idea-ology. Karl Marx (1818–83) used ideology to refer to ideas that serve the interests of the ruling class by concealing the contradictions of class society, thereby promoting false consciousness and political passivity amongst subordinate classes. In this view a clear distinction can be drawn between ideology and science, representing falsehood and truth respectively. Later Marxists adopted a neutral concept of ideology, regarding it as the distinctive ideas of any social class, including the working class. Some liberals, particularly during the Cold War period, have viewed ideology as an officially sanctioned belief system that claims a monopoly of truth, often through a spurious claim to be scientific. Conservative thinkers have sometimes followed Michael Oakeshott (1901–90) in treating ideologies as elaborate systems of thought that orientate politics towards abstract principles and goals and away from practical and historical circumstances.

Significance

The concept of ideology has had a controversial career. For much of its history, ideology has carried starkly pejorative implications, being used as a political weapon to criticise or condemn rival political stances. Indeed, its changing significance and use can be linked to shifting patterns of political antagonism. Marxists, for example, have variously interpreted *liberalism, *conservatism and *fascism as forms of ‘bourgeois ideology', committed to the mystification and subordination of the oppressed proletariat. Marxist interest in ideology, often linked to Antonio Gramsci's (1891–1937) theory of ideological *hegemony, grew markedly during the twentieth century as Marxist thinkers sought to explain the failure of Marx's prediction of proletarian revolution. The advent of the Cold War in the 1950s encouraged liberal theorists to identify similarities between fascism and *communism, both being inherently repressive ‘official' ideologies which suppressed opposition and demanded regimented obedience. However, the 1950s and 1960s also witnessed growing claims that ideology had become superfluous and redundant, most openly through the ‘end of ideology' thesis advanced by Daniel Bell (1960) . This view reflected not only the declining importance in the West of ideologies such as communism and fascism, but also the fact that similarities between liberalism, conservatism and *socialism had apparently become more prominent than their differences.

Nevertheless, the proclaimed demise of ideology has simply not materialised. Since the 1960s, ideology has been accorded a more important and secure place in political analysis for a number of reasons. First, the wider use of the social-scientific definition of ideology means that the term no longer carries political baggage and can be applied to all ‘isms' or action-orientated political philosophies. Second, a range of new ideological traditions have steadily emerged, including *feminism and *ecologism in the 1960s, the *New Right in the 1970s and *religious fundamentalism in the 1980s. Third, the decline of simplistically behavioural approaches to politics has led to growing interest in ideology both as a means of recognising how far political action is structured by the beliefs and values of political actors, and as a way of acknowledging that political analysis always bears the imprint of values and assumptions that the analyst himself or herself brings to it.

| <== previous lecture | | | next lecture ==> |

| HUMAN NATURE | | | LEFT/RIGHT |