Communication: Models, Perspectives

Date: 2015-10-07; view: 474.

UNIT 2

3. _______________________________?

2. _______________________________?

1. _____________________________?

Ex.23. Look at the following answers given by Dr. Philip Kotler. Try to guess what the original questions are.

Ex.22. Answer the questions.

1. What is marketing-mix?

2. What are the main elements of the marketing mix?

3. What is maturity in the product life cycle?

4. Who suggested that a product should be viewed on three levels: core, actual and augmented product?

5. What is a target audience?

6. What model is shift the focus from the producer to the consumer?

7. What factors are pricing should take into account?

8. Which companies use model Four C's model?

Marketing is the science and art of exploring, creating, and delivering value to satisfy the needs of a target market at a profit. Marketing identifies unfulfilled needs and desires. It defines, measures and quantifies the size of the identified market and the profit potential. It pinpoints which segments the company is capable of serving best and it designs and promotes the appropriate products and services.

Marketing is often performed by a department within the organization. This is both good and bad. It's good because it unites a group of trained people who focus on the marketing task. It's bad because marketing activities should not be carried out in a single department but they should be manifest in all the activities of the organization.

In my 11th edition of Marketing Management, I describe the most important concepts of marketing in the first chapter. They are: segmentation, targeting, positioning, needs, wants, demand, offerings, brands, value and satisfaction, exchange, transactions, relationships and networks, marketing channels, supply chain, competition, the marketing environment, and marketing programs. These terms make up the working vocabulary of the marketing professional.

Marketing's key processes are: (1) opportunity identification, (2) new product development, (3) customer attraction, (4) customer retention and loyalty building, and (5) order fulfillment. A company that handles all of these processes well will normally enjoy success. But when a company fails at any one of these processes, it will not survive.

Marketing started with the first human beings. Using the first Bible story as an example (but this was not the beginning of human beings), we see Eve convincing Adam to eat the forbidden apple. But Eve was not the first marketer. It was the snake that convinced her to market to Adam.

Marketing as a topic appeared in the United States in the first part of the 20th century in the teaching of courses having to do with distribution, particularly wholesaling and retailing. Economists, in their passion for pure theory, had neglected the institutions that help an economy function. Demand and supply curves only showed where price may settle but do not explain the chain of prices all the way from the manufacturer through the wholesalers through the retailers. So early marketers filled in the intellectual gaps left by economists. Nevertheless, economics is the mother science of marketing.

At least three different answers have been given to this question. The earliest answer was that the mission of marketing is to sell any and all of the company's products to anyone and everyone. A second, more sophisticated answer, is that the mission of marketing is to create products that satisfy the unmet needs of target markets. A third, more philosophical answer, is that the mission of marketing is to raise the material standard of living throughout the world and the quality of life.

Marketing's role is to sense the unfulfilled needs of people and create new and attractive solutions. The modern kitchen and its equipment provide a fine example of liberating women from tedious housework so that they have time to develop their higher capacities.

How Models Help Us Understand Communication

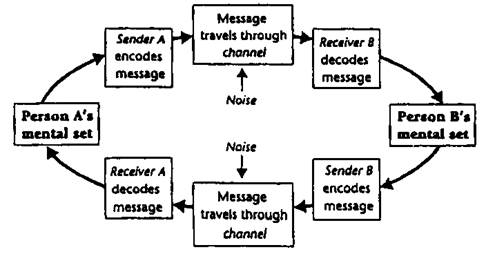

In addition to defining communication, scholars also build models of it. A model is an abstract representation of a process, a description of its structure or function.

Models aid us by describing and explaining a process, by yielding testable predictions about how the process works, or by showing us ways to control the process. Some models fulfill an explanatory function by dividing a process into constituent parts and showing us how the parts are connected. A city's organizational chart does this by explaining how city government works, and the sociological description allows us to see the economic and social factors that caused the city to become what it is today.

Other models fulfill a predictive function. Traffic simulations and population growth projections function in this way. They allow us to answer “if. . . then” questions. If we add another traffic light, then will we eliminate gridlock? If the population keeps growing at the current rate, then what will housing conditions be in the year 2020? Models help us answer questions about the future.

Finally, models fulfill a control function. A street map not only describes the layout of a city but also allows you to find your way from one place to another and helps you figure out where you went wrong if you get lost. Models guide our behavior. They show us how to control a process.

Models are useful, but they can also have drawbacks. In building and using models, we must be cautious. First, we must realize that models are necessarily incomplete because they are simplified versions of very complex processes. When a model builder chooses to include one detail, he or she invariably chooses to ignore hundreds more.

Second, we must keep in mind that there are many ways to model a single process. Unfortunately, when we study complex processes, we can never be one hundred percent certain we understand them. There are many “right answers,” all equally valuable but each distinct. Although this may be confusing at first, try thinking of it positively. Looking for single answers limits you intellectually; accepting multiple answers opens you to new possibilities.

Finally, we mustn't forget that models make assumptions about processes. It's always important to look “below the surface” of any model to detect the hidden assumptions it makes.

It All Depends on Your Point of View: Three Perspectives

A perspective is a coherent set of assumptions about the way a process operates. The first three models we will look at are built on different sets of assumptions. The first model takes what is known as a psychological perspective. It focuses on what happens “inside the heads” of communicators as they transmit and receive messages. The second model takes a social constructionist perspective. It sees communication as a process whereby people, using the tools provided by their culture, create collective representations of reality. It emphasizes the relationship between communication and culture. The third model takes what is called a pragmatic perspective. According to this view, communication consists of a system of interlocking, interdependent “moves,” which become patterned over time. This perspective focuses on the games people play when they communicate.

Communication as Message Transmission

Most models and definitions of communication are based on the psychological perspective. They locate communication in the human mind and see the individual as both the source of and the destination for messages. Figure 2.1 illustrates an example of a psychological model.

In a psychological model, messages are filtered through an individual's store of beliefs, attitudes, values, and emotions.

Figure 2.1 – The Psychological Model of Communication

Elements of a Psychological Model

The model in Figure 2.1 depicts communication as a psychological process whereby two (or more) individuals exchange meanings through the transmission and reception of communication stimuli. According to this model, an individual is a sender/receiver who encodes and decodes meanings. John has an idea he wishes to communicate to Clare. John encodes this idea by translating it into a message that he believes Clare can understand. The encoded message travels along a channel, its medium of transmission, until it reaches its destination. Upon receiving the message, Betty decodes it and decides how she will reply. In sending the reply, she gives Adam feedback about his message. Adam uses this information to decide whether or not his communication was successful.

During encoding and decoding, John and Clare filter messages through their mental sets. A mental set consists of a person's beliefs, values, attitudes, feelings, and so on. Because each message is composed and interpreted in light of an individual's past experience, each encoded or decoded message has its own unique meaning. Of course, partners' mental sets can sometimes lead to misunderstandings. The meanings John and Clare assign to a message may vary in important ways. If this occurs, they may miscommunicate. Communication can also go awry if noise enters the channel. Noise is any distraction that interferes with or changes a message during transmission. Communication is most successful when individuals are “of the same mind” – when the meanings they assign to messages are similar or identical.

Let's look at how this process works in a familiar setting, the college lecture. Professor Brown wants to inform his students about the history of rhetoric. Alone in his study, he gazes at his plaster-of-Paris bust of Aristotle and thinks about how he will encode his understanding and enthusiasm in words. To encode successfully, he must guess about what's going on in the students' minds. Although it's hard for him to imagine that anyone could be bored by the history of rhetoric, he knows students need to hear a “human element” in his lecture. He therefore decides to include examples and anecdotes to spice up his message.

Brown delivers his lecture in a large, drafty lecture room. The microphone he uses unfortunately emits shrill whines and whistles at inopportune times. That he also forgets to talk into the mike only compounds the noise problem. Other sources of distraction are his appearance and nonverbal behavior. When Brown enters the room, his mismatched polyester suit and hand-painted tie are fairly presentable, but as he gets more and more excited, his clothes take on a life of their own. His shirt untucks itself, his jacket collects chalk dust, and his tie juts out at a very strange angle. In terms of our model, Smith's clothes are too noisy for the classroom.

Despite his lack of attention to material matters and his tendency toward dry speeches, Brown knows his rhetoric, and highly motivated students have no trouble decoding the lecture. Less-prepared students have more difficulty, however. Brown's words go “over their heads.” As the lecture progresses, the students' smiles and nods, their frowns of puzzlement, and their whispered comments to one another act as feedback for Smith to consider.

Brown's communication is partially successful and partially unsuccessful. He reaches the students who can follow his classical references but bypasses the willing but unprepared students who can't decode his messages. And he completely loses the seniors in the back row who are taking the course pass/fail and have set their sights on a D minus. Like most of us, some of the time Brown succeeds, and some of the time he fails.

Improving Faulty Communication

According to the psychological model, communication is unsuccessful whenever the meanings intended by the source differ from the meanings interpreted by the receiver. This occurs when the mental sets of source and receiver are so far apart that there is no shared experience; when the source uses a code unfamiliar to the receiver; when the channel is overloaded or impeded by noise; when there is little or no opportunity for feedback; or when receivers are distracted by competing internal stimuli.

Each of these problems can be solved. The psychological model points out ways to improve communication. It suggests that senders can learn to see things from their receivers' points of view. Senders can try to encode messages in clear, lively, and appropriate ways. They can use multiple channels to ensure that their message gets across, and they can try to create noise-free environments. They can also build in opportunities for feedback and learn to read receivers' nonverbal messages.

Receivers too can do things to improve communication. They can prepare themselves for a difficult message by studying the subject ahead of time. They can try to understand “where the speaker is coming from” and anticipate arguments. They can improve their listening skills, and they can ask questions and check their understanding. All of these methods of improving communication are implicit in the model in Figure 2.1.

Criticizing the Psychological Perspective

Although the psychological model is by far the most popular view of communication, it poses some problems, which arise from the assumptions the psychological perspective makes about human behavior.

First, the psychological model locates communication in the psychological processes of individuals, ignoring almost totally the social context in which communication occurs, as well as the shared roles and rules that govern message construction.

Second, in incorporating the ideas of channel and noise, the psychological model is mechanistic. It treats messages as though they are physical objects that can be sent from one place to another. Noise is treated not as a message, but as a separate entity that “attacks” messages. The model also assumes that it is possible not to communicate, that communication can break down.

Finally, the psychological model implies that successful communication involves a “meeting of the minds.” The model suggests that communication succeeds to the extent that the sender transfers what is in his or her mind to the mind of the receiver, thereby implying that good communication is more likely to occur between people who have the same ideas than between those who have different ideas. This raises some important questions: Is it possible to transfer content from one mind to another? Is accuracy the only value we should place on communication? Is it always a good idea to seek out people who are similar rather than different? Some critics believe the psychological model diminishes the importance of creativity.

| <== previous lecture | | | next lecture ==> |

| Ex.20. Match the right explanation to the each type of promotion. | | | CONTRACT: DELIVERY DATES. MARKING and PACKING |