The Rise of the Super brands

Date: 2015-10-07; view: 545.

Text 3

Can Procter & Gamble's $54 billion merger with Gillette kick-start growth in the consumer-goods industry?

EVERY industry has its golden age. The makers of packaged consumer goods—quilted paper towels, tinned baked beans and other household essentials—enjoyed theirs around the middle of the 20th century. In the 1950s and 1960s, companies such as General Mills, Unilever and Procter & Gamble were delighting their customers with one innovative new product after another, from fluoride-enhanced toothpastes to fragrant fabric softeners and disposable nappies. But the industry's youthful vigour has ebbed away. Mr Clean, the bald, rugged sailor who fronts a line of domestic-cleaning products for P&G, turns 47 this year. (The chap has had a rejuvenating name change, however: he used to be called Mr Veritably Clean.)

One consumer-goods company that has fought as heroically as any against the onset of middle-age lethargy is P&G. In the past five years, the firm that was founded in Cincinnati in 1837 by William Procter, an English candlemaker and James Gamble, an Irish soap manufacturer, has boosted innovation, ditched losing brands, bought winning ones and stripped away some of the bureaucracy that has slowed its starch-shirted army of 110,000 “Proctoids”.

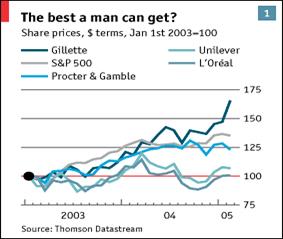

As P&G's share price has recaptured a little of its bounce (see chart 1), Alan (“A.G.”) Lafley, a dapper beauty-products specialist who became boss in June 2000, has grown bolder. On January 28th, he announced his company was buying Gillette—a maker of razors, shaving foam and other grooming products, as well as batteries and toothbrushes—for just over $50 billion. Stockmarket analysts and industry gurus whooped with delight. Mr Lafley called the deal a “unique opportunity” and a “terrific fit”. Gillette's boss, James Kilts (who will become a vice-chairman of the combined firm, and who stands to net more than $150m from the deal) said the merger would create “the potential for superior sustained growth”.

Even more fulsome in his praise was Warren Buffett, whose investment company, Berkshire Hathaway, owns nearly 10% of Gillette's shares. This “dream deal” would create “the greatest consumer-products company in the world”, he chortled, promising to invest more in the new firm.

The combined company will certainly be the biggest in its industry: it will have annual salesof more than $60 billion and a workforce that will top 140,000. But will it also be the best? Has Mr Lafley discovered among his shampoos, face creams and hair dyes an elixir of youth?

As Barbara Hulit of the Boston Consulting Group points out, the consumer-goods industry has found itself caught between slowing sales, rising costs and waning pricing power. Over the past five years, calculates Ms Hulit, the sales of the consumer-goods companies included in the S&P 500 index of big American companies have grown at a compound annual rate of just 4.7%. Meanwhile, their sales, general and administrative expenses have been rising by 5% a year.

Even with careful stewardship, the sales of mature brands tend to slip back towards their “natural” growth rate—population growth, plus inflation. P&G pioneered fabric softeners in the 1960s and scented sheets for tumble dryers in the 1970s. The industry introduced detergents as long ago as the 1930s. King Gillette founded the American Safety Razor Company in Boston in 1901. Ivory, a P&G-branded soap, traces its serendipitous history back to 1879, when James Gamble, son of the founder and a trained chemist, accidentally cooked up an unusually pure, floating soap in his laboratory.

Commodity prices have risen sharply recently, pushing up the cost of the foodstuffs, chemicals, packaging and energy that go into making the industry's products. There was a time when consumer-goods firms could pass rising costs on to their customers. But the spread of aggressive, big-box retail chains such as Wal-Mart (whose strategy is built around passing on savings won from suppliers to its shoppers), Carrefour and Costco has destroyed much of the industry's pricing power.

Meanwhile, retailers have begun plugging their own discounted, “private label” brands that compete with the pricier, higher-margin products from Unilever and P&G. As retailers have grown in clout, they have also squeezed the consumer-goods firms for more “trade spending”—the money the likes of P&G must stump up for in-store promotion, displays and eye-level shelf space. About 17% of the consumer-goods industry's sales disappear into such trade spending, says Ms Hulit.

Meanwhile, the complexity of advertising, marketing and distributing branded consumer goods has soared, further pushing up costs. P&G is the world's biggest advertiser, with a budget of around $3 billion last year. A decade ago, 90% of its global advertising spending went on television. Today, for some products only about a quarter of the budget is spent on television. The audience for traditional media is fragmenting, making consumers harder and more expensive to reach. So, along with other consumer-goods companies, P&G is finding that so-called “below-the-line” forms of marketing, such as in-store promotions, posters, coupons and sponsorship, are often more effective.

| <== previous lecture | | | next lecture ==> |

| Ex 1 make up top sentences to each paragraph of Text 2. | | | Hair today |